Wildland Firefighting Resources Hub

Wildland fire is a growing operational reality. With fire seasons stretching longer and burn intensities growing stronger, the U.S. wildland firefighting system is under pressure like never before. And for fire investigators working alongside suppression crews, understanding that system, its structure, its limitations, and its tactical resources, is essential.

In this wildland firefighting resources guide, we’ll unpack every layer of the system: interagency command structures, federal and state roles, ICS deployment models, resource typing, crew types, aerial support, technology stacks, and the logistical underbelly of it all.

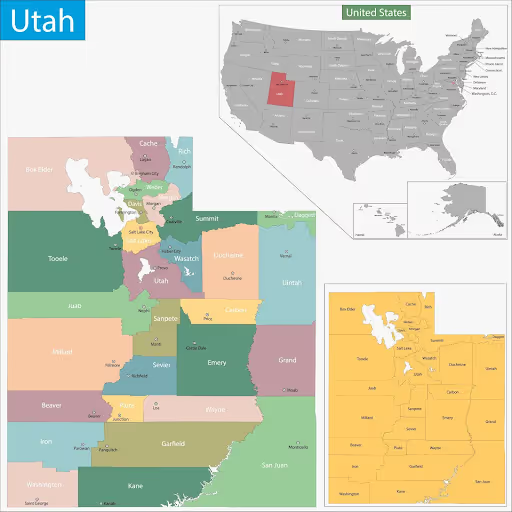

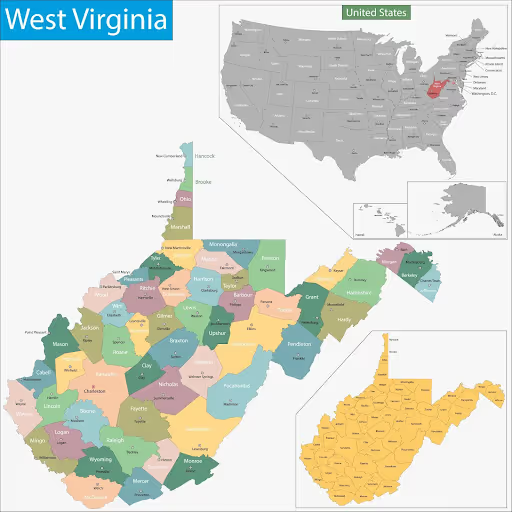

Wildland Firefighting Resources by State

Each state maintains its own wildland fire management agencies and resources, often collaborating with federal partners. These state agencies play crucial roles in initial attack and extended suppression efforts.

Federal Agencies and Their Roles

Wildland fire management in the United States is governed by a complex but well-defined federal framework. Each agency brings its own authorities, mandates, funding channels, and tactical approaches. For fire investigators operating on federal, tribal, or mixed jurisdiction incidents, understanding this is important to get the job done right.

This section outlines the five primary federal agencies with wildland fire jurisdiction, what they’re responsible for, how they interact with each other, and what that means for investigative coordination.

1. U.S. Forest Service (USFS)

Under the Department of Agriculture, the USFS manages over 193 million acres of national forests and grasslands. It is by far the largest federal firefighting entity.

The Forest Service operates under the Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy and manages suppression efforts on its lands through regional coordination centers (RCCs) and forest-level dispatch centers.

Investigative implications:

- Most Type 1 and Type 2 incidents involving federal land are USFS-led, especially in the Western U.S.

- USFS fire investigators follow FSM 5100 and FIRECAUSE protocols, which align with NWCG guidelines but include agency-specific documentation requirements.

- Any ignition on USFS land (even if it spreads off) generally triggers USFS jurisdiction over cause determination.

2. Bureau of Land Management (BLM)

Part of the Department of the Interior, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) manages 245 million acres of public lands, primarily rangelands and desert environments in the West.

BLM prioritizes rapid initial attack on low-complexity fires and works extensively with local VFDs and state partners under cooperative agreements.

Investigative implications:

- BLM is often the host agency in remote ignition areas with sparse infrastructure, where evidence is fragile or burned over quickly.

- Investigators must work closely with local sheriffs and rural cooperator fire chiefs, especially in Utah, Nevada, and eastern Oregon.

- BLM’s fire investigation handbook mirrors NWCG guidance but emphasizes chain-of-custody documentation for resource protection cases (e.g., grazing rights, arson damage to grazing lands).

3. National Park Service (NPS)

NPS manages over 85 million acres, including iconic national parks, monuments, and heritage sites.

Unlike other federal agencies, NPS often uses prescribed fire and fire-use strategies to preserve ecological processes. Suppression decisions are influenced by cultural resource protection and visitor safety.

Investigative implications:

- Investigators on NPS lands must consider historic preservation laws, which may affect evidence recovery methods.

- Expect direct coordination with NPS law enforcement rangers for ignition sources with potential criminal liability (e.g., negligence, campfire bans).

- NPS units may delay suppression in designated fire-use zones; this can affect how origin areas evolve over time.

4. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS)

FWS oversees the National Wildlife Refuge System, which has approximately 95 million acres focused on habitat conservation.

FWS fire teams are generally smaller, and fires often occur in wetlands, coastal zones, or critical wildlife habitat. Their response prioritizes resource preservation, sometimes even above full suppression.

Investigative implications:

- Fires on FWS land often involve complex jurisdictional overlap (adjacent private lands, tribal hunting grounds, state game preserves).

- Suppression activities may be limited to containment, not full extinguishment, which impacts fire pattern preservation.

- Investigators should coordinate early with refuge managers to understand access constraints and habitat sensitivity before digging or clearing.

5. Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA)

BIA provides wildland fire management services to 574 federally recognized tribes across 56 million acres of Indian land.

BIA operates under the Branch of Wildland Fire Management and coordinates closely with tribal governments. Fires on trust lands are managed per tribal MOU or interagency agreements.

Investigative implications:

- All fire investigations on tribal lands must be conducted with tribal consent and in accordance with sovereign governance.

- Investigators may need to coordinate with tribal law enforcement, BIA police, and federal agents (ATF or FBI) depending on the ignition source.

- Cultural sensitivity is paramount. Artifact disturbance or mishandling of sacred sites during evidence recovery can result in delays in federal investigations or legal issues.

National Interagency Coordination

The NIFC, based in Boise, Idaho, serves as the central hub for coordinating wildland firefighting efforts across the nation. It houses the National Interagency Coordination Center (NICC), which allocates resources and manages national-level incidents.

The National Multi-Agency Coordination Group (NMAC) operates within NIFC to establish national preparedness levels and prioritize resource allocation during periods of high fire activity.

Agencies housed at NIFC include:

- U.S. Forest Service (USFS)

- Bureau of Land Management (BLM)

- National Park Service (NPS)

- Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS)

- Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA)

- National Weather Service (fire meteorologists)

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)

- National Association of State Foresters (NASF)

- U.S. Fire Administration (USFA)

For fire investigators, this means you’re operating under an umbrella that coordinates everything from your helibase contract to the arrival of an ATF-certified investigator on a federal incident.

Incident Command System (ICS) Structure

The Incident Command System (ICS) is more than a response framework. It’s the operational backbone of wildland fire management in the United States. Designed for scalability, ICS allows agencies at every level (federal, state, tribal, and local) to integrate seamlessly under a unified structure, regardless of incident size, jurisdiction, or complexity.

Incidents are classified into five types:

- Type 5: Local response, resolved within a few hours, no formal ICS structure beyond initial attack (IA). Often handled by a single engine or crew.

- Type 4: Slightly more complex. It may extend beyond one operational period but is still managed at the local level with minimal ICS roles activated.

- Type 3: Extended attack requiring an ICS structure with a command and general staff. May include multiple divisions, night ops, and resource tracking.

- Type 2: Significant resource commitment and multi-day operations. A Type 2 IMT (Incident Management Team) is brought in; it often includes federal oversight.

- Type 1: The most complex incidents — large fires with major infrastructure, WUI involvement, evacuations, and heavy media/political attention. Managed by a Type 1 IMT with full overhead and advanced logistics.

Fire investigators must adapt their operations to the complexity level. On Type 1 and 2 incidents, coordination with the Planning Section and Operations Section becomes essential, especially when documenting evidence or requesting special support (drones, fire behavior analysts, or safety officers).

Wildland Firefighting Resources

Wildland fire suppression is a coordinated effort requiring diverse, highly trained personnel and specialized equipment, each with specific tactical functions.

Understanding the deployment, limitations, and strengths of these resources helps fire investigators interpret suppression patterns, flame behavior, and the timing of fire movement across terrain.

Ground-Based Suppression Teams

- Hand Crews (Type 1 or 2): Typically 20-person teams trained to construct control lines, perform burnout operations, mop-up, and secure perimeters. Type 1 crews (often hotshots) are more experienced and self-sufficient in remote terrain.

- Hotshot Crews (IHCs): Elite 20-person crews trained for direct attack in rugged, high-risk areas. Hotshots often work at the heel or flanks of fast-moving fires and can engage without engine or aerial support. Their locations on the fireline are critical when reconstructing origin zones or suppression timelines.

- Smokejumpers: Wildland firefighters trained to parachute into remote fires. They are typically first on the scene in isolated locations. Investigators should review jump spot coordinates and deployment logs to determine initial suppression attempts and their potential impact on origin preservation.

- Engine Crews: Operate wildland engines (Type 3–6) and supply water directly to the fireline. Engine reports, hose lay maps, and water source logs can aid in reconstructing suppression flow and footprint.

- Helitack Crews: Helicopter-deployed teams used for rapid response and recon. They often perform bucket drops, sling load operations, and remote insertions. Investigators should verify helibase logs and flight tracking to understand drop locations and rotorwash effects on light fuels or evidence sites.

Aerial Resources

- Fixed-Wing Airtankers: Deliver long-term retardant or water to slow fire spread. Includes LATs (Large Airtankers) and VLATs (Very Large Airtankers) such as DC-10s.

- Helicopters: Used for bucket drops (Bambi Buckets), recon, hoist rescues, and aerial ignition (via plastic sphere dispensers). Important to note flight altitude, drop intervals, and pilot reports when assessing burn patterns in the origin area.

Aerial resource use is coordinated through Air Attack Group Supervisors (ATGS) and tracked via air-to-ground logs and ICS-220 forms.

Training and Qualification Standards

Wildland fire qualifications are standardized through the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG), which publishes national position standards and manages interagency training curricula. Every firefighter and overhead position, including investigators (INVF), must meet specific training, task book, and experience requirements documented in PMS 310-1.

NWCG position standards:

- INVF (Fire Investigator): Requires completion of FI-210 (Wildland Fire Origin & Cause Determination), annual refresher training, and a position task book (PTB) signed off under qualified supervision.

- Red Book: Each agency’s Fireline Handbook includes operational guidance, suppression standards, and safety protocols that investigators must follow during incidents.

Training infrastructure:

- Wildland Fire Learning Portal (WFLP): Central access point for online courses, instructor-led sessions, and qualification tracking. Investigators use WFLP to complete refreshers, review new job aids, and access documentation like the IRPG (Incident Response Pocket Guide).

- IQCS (Interagency Qualifications and Certification System) and IQS (Incident Qualification System): Federal and state-level databases for tracking qualifications, currency, and certifications. Investigators must ensure their records are current, especially before deployment to Type 1 or 2 incidents.

Investigative-specific guidance:

Key references every investigator should have downloaded or printed:

- NWCG G-09 (Guide to Wildland Fire Origin and Cause Determination)

- FI-210 Student Manual (for field review)

- IRPG 2025 Edition: Incident Response Pocket Guide

Investigator credibility in court and across agencies begins with verified qualifications. Every scene entry, interview, and report submission assumes you're operating with up-to-date credentials and methodology.

Technology and Data Systems

Modern wildland firefighting is as much about data as it is about boots on the ground. As fire behavior grows more erratic, agencies rely heavily on geospatial tools, cloud-based platforms, and real-time resource tracking to guide operational decisions and strategic planning.

- LANDFIRE Program: A joint effort between the U.S. Forest Service and the Department of the Interior, LANDFIRE provides spatial datasets on vegetation, fuels, and disturbance history. Fire behavior analysts and investigators use LANDFIRE layers for modeling spread, verifying fuel load classifications, and planning prescribed burns.

- Resource Ordering and Status System (ROSS): This centralized system manages the movement and status of thousands of personnel, engines, aircraft, and overhead positions. It’s how dispatch knows where every resource is, and how IMTs request what they need. ROSS also helps investigators track when a resource was mobilized or demobilized, which is critical when reconstructing timelines or validating reports.

- IRWIN (Integrated Reporting of Wildland Fire Information) and WFDSS (Wildland Fire Decision Support System) also play key roles. IRWIN feeds incident data across systems (dispatch, e-ISuite, ICS-209), while WFDSS captures agency administrator intent and risk-informed decision-making, often before investigators even arrive on scene.

Together, these tools improve situational awareness, justify suppression decisions, and preserve the digital footprint of every significant fire.

Private Sector and Non-Governmental Support

Federal and state agencies don’t fight fire alone. Increasingly, private contractors and nonprofit organizations provide critical surge capacity and ecological expertise in both suppression and mitigation.

- National Wildfire Suppression Association (NWSA): Represents over 300 private companies supplying Type 6 engines, hand crews, fallers, EMTs, and even incident overhead. These contractors are mobilized under federal EERA agreements or state compacts and are often first in on IA when local agencies are short.

- The Nature Conservancy (TNC): Plays a vital role in ecological fire planning, especially on prescribed burns. Their fire crews, burn bosses, and partnerships with indigenous fire practitioners are helping shift the national conversation toward pre-suppression and fuels management. TNC also helps train non-agency firefighters through cooperative burn units.

Private resources may not follow agency documentation standards unless explicitly directed, and NGO-led burns may require different investigative considerations if they escape prescription.

Health and Wellbeing of Firefighters

Recognizing the physical and mental demands of wildland firefighting, federal agencies are developing comprehensive health and well-being programs:

- Mental Health Initiatives: Programs such as Crew Cohesion Counseling Models and Behavioral Health Support Modules on Incident Management Teams (IMTs) are being implemented to address stress and trauma.

- Physical Health Measures: Expanded rehabilitation protocols and state-level presumptive illness legislation are in place to support firefighters' physical health.

These initiatives aim to provide support tailored to the unique experiences and needs of firefighters, addressing issues such as fatigue, stress, and long-term health impacts.

Key Wildland Firefighting Takeaways for Fire Investigators

Wildland fire in the United States is no longer confined to remote canyons or drought-stricken timber stands. It's a national, year-round challenge that is stretching resources, reshaping suppression tactics, and redefining investigative responsibilities.

As an investigator, your work begins with understanding how incidents are managed, how resources are mobilized, and how federal, state, and private systems intertwine. Whether you're responding to a 20-acre grass fire or embedded in a Type 1 IMT on a 100,000-acre complex, your effectiveness hinges on more than scene analysis. It depends on context, coordination, and command fluency.